Open Book 2017: “Writing is not about saying the right thing”

02 Oct 2017

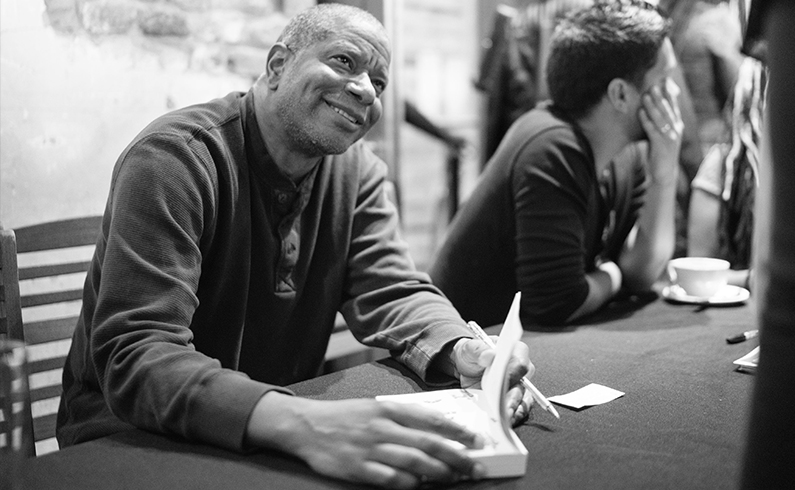

Pictured: Man Booker Prize winner Paul Beatty signs copies of his book The Sellout. Photo credit: Retha Ferguson, courtesy of Open Book Festival.

‘The Sellout’ was one of the two talks at the 2017 Open Book Festival that were presented by PEN South Africa, the other was ‘Women’s Manifesto‘ with PEN SA President Nadia Davids, Board Member Gabeba Baderoon, Sindiswa Busuku-Mathese and Buhle Ngaba.

By Rachel Zadok

Open Book Festival, Thursday night, 7.45pm. Streetlights illuminate the drizzle falling on to Cape Town’s parched streets. Inside the Fugard Theatre, there is an air of tension. Harry Garuba stalks the stage, holding a sheaf of notes, lips moving in silent preparation. His hair glistens with tiny droplets of condensation, maybe rain, maybe perspiration. He seems nervous, and who could blame him? Professor Garuba may be Head of Department and Associate Professor in the Centre for African Studies at the University of Cape Town, but he’s about to share the stage with Paul Beatty, author of The Sellout. It’s a novel that is both controversial and acclaimed. In 2015, it won the coveted National Book Critics Circle Award for fiction. A year later, The Sellout became the first American novel to win the Man Booker Prize, for which all English-language novels became eligible two years earlier.

The Sellout chronicles an urban farmer who tries to spearhead a revitalisation of slavery and segregation in a fictional Los Angeles neighbourhood, Dickens. Flavorwire’s non-fiction editor, Elisabeth Donnelly, described it as “a masterful work that establishes Beatty as the funniest writer in America“, while Reni Eddo-Lodge, author of Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race, called it a “whirlwind of a satire“.

The Sellout took over five years to write and was rejected 18 times. In the current state of American race relations, where movements like #BlackLivesMatter provide a vital counter narrative to Trump’s America, the reluctance of some publishers to take a chance on a book is perhaps understandable. Consider the opening sentence:

“This may be hard to believe, coming from a black man, but I’ve never stolen anything. Never cheated on my taxes or at cards. Never snuck into the movies or failed to give back the extra change to a drugstore cashier indifferent to the ways of mercantilism and minimum-wage expectations. I’ve never burgled a house. Held up a liquor store. Never boarded a crowded bus or subway car, sat in a seat reserved for the elderly, pulled out my gigantic penis and masturbated to satisfaction with a perverted, yet crestfallen, look on my face.”

“There’s a thin line between satire and offence.” – Harry Garuba

Introducing Beatty and his work to a sold out auditorium, Harry Garuba says of The Sellout: “Sometimes a book wins a prize, and you try to read it, but you can’t, because you don’t know what the judges were looking at. But this is a book that once you pick it up, you really can’t drop it.” He goes on to point out that “there is a thin line between satire and offence” and that he read the book with an eye on how Beatty managed to balance the satirical and the offensive. For his opening question, Garuba turns his focus to an essay Beatty wrote, where he spoke of the black literary tradition being one of sobriety, and that one has to go out of one’s way to find African American writers who practice a tradition of insobriety.

“A lot of African American writers, artist, creators constantly try to prove their humanity,” says Beatty. “So much of that is what kind of human am I going to prove myself, ourselves, to be. Oftentimes it’s a sober, thinking, smart, perfectionist [person], a straw person who doesn’t really exist.” Beatty went on to clarify that he doesn’t necessarily think the tradition is one based on sobriety, but a lot of the literature that gets passed along scholastically is. Langston Hughes is an example. “It’s a shame that we take this one very sober, asexual portrait that Langston Hughes presents. I know a couple of black people who are not like this,” he says, laughing.

In writing The Sellout, Beatty was trying to look beyond expectations of what a black book is supposed to be, but it’s also about what a book could do. “For a couple of years, I’ve been thinking about [if it’s] possible to write a book in the States that people would ban. I didn’t try to write a book that would be banned, but I did try to push some kind of boundary and explore what those boundaries are.”

Apartheid is mentioned several times in the book, and though this is Beatty’s first visit to South Africa, he has been aware of Apartheid since he was a child in the 1970s. He recalls watching the Miss Universe contest, and the outrage of his friend’s mother at the fact that Miss South Africa was white. It made him think.

Garuba brings up the topic of blackface, about which Beatty seems conflicted. He says there are no hard and fast rules. “What’s the right degree of sensitivity?” he asks. “I don’t know, I’m figuring it out for myself.”

The Sellout and Beatty’s life intersect in the relationship Me, the novel’s main protagonist, has with his father. The father, a psychologist who uses Me to conduct social experiments, is based on Beatty’s own mother “My mom is nuts,” he says. “Me and my sisters are all left handed, and there aren’t other left handed people in our family. My mom swears she tied our right hands behind our backs when we were little. My sister’s don’t believe her, but I believe her.” For two years, Beatty’s mother tried to raise him and his siblings as Japanese. So they were sort of experimented on. “There’s also the notion of trying to raise someone bulletproof in a society that’s literally and figuratively shooting at them.”

The conversation between Beatty and Garuba is one of two events at the Open Book Festival presented by PEN South Africa, whose banner on the stage between Beatty and Garuba is emblazoned with the call to action ‘Write! Africa, Write!’ It’s fitting then that Garuba asks Beatty, who teaches at Columbia University, about the value of teaching creative writing.

It’s helpful to listen to other writers speak about their work. It’s more about giving people time to write than teaching them to write, to give them space to be critical, but not judgemental. A space that’s really open, so that they can say what they want to say. He gives an example of a paper one of his student’s wrote about a black character raping a white character. “Can anyone write a story about a black guy raping a white woman?” Beatty asks. The answer is yes, but this particular story angered his students because it felt inevitable. It fell into a pattern. It wasn’t that this couldn’t happen, but the way the student had told it was based on how we all think it happens. “It’s not that you can’t step on those landmines, but you need to think if you want to do it. It’s a level of consideration. Most of us are good people, we want to do the right thing, say the right thing, but story writing is not about saying the right thing.”